By Siddharth Jejurikar ’16, Entertainment Editor

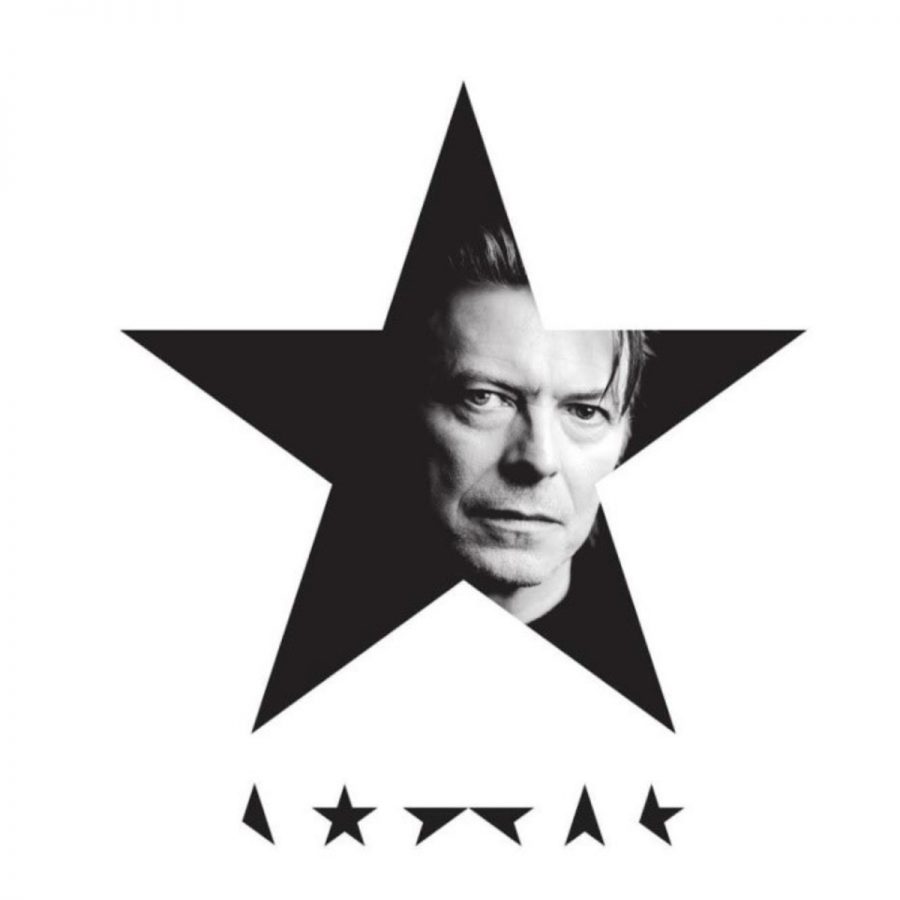

On January 10th 2016, two days after the release of his final album, Blackstar, and his 69th birthday, David Bowie lost his battle with liver cancer. With his passing, the world lost not only a musical icon but also a living testament to artistic integrity. His image and personal life were representations of his uncompromising artistic vision of true freedom. This is a freedom that exists only outside the barriers of the mundane societal norms that dictate a typical person’s fashion, sexuality, and mannerisms. Musically, David Bowie worked barely inside the fringes, that vital area that bridges that gap of relatability and experimentalism. His skills as a multi-instrumentalist and dazzling stage-performer made him a poster-child of the glam-rock movement long with Elton John, Kiss, and Queen. Blackstar is in many ways a sort of last will and testament for Bowie, showing the world what kind of legacy he hoped to leave behind.

Key influences from jazz and experimental-electronic music permeate the record and its seven distinct tracks. Programed drums and synthetic textural affects, on Bowie’s voice and beyond, lay a backing for emotional and ominous guitar riffs and intermittent saxophone soloing. This is mostly thanks to the collaborative work of James Murphy, founder of LCD Soundsystem. In an interview prior to the album’s release, the album’s producer, Tony Visconti, cited influences from the recent 2015 hip-hop record To Pimp a Butterfly by Kendrick Lamar and experimental electronic garage rap group, Death Grips. It’s clear now that the manifestation of these influences was the jazzy-electronic style that this album holds. Bowie’s simultaneous use of live and computerized instrumentation serves to paint the same intentionally conflicted picture that the song’s lyrics themselves pose. The raw humanistic power of a saxophone or guitar is distorted by the ominous lifelessness of a synthesizer’s hum on tracks like “Blackstar”, painting a dark and broken image that still manages to feel real. This contrast is continued on a grander scale between the tracks themselves, with “Dollar Days” resembling a rock ballad while “Blackstar” is more akin to an occult prayer. Possibly a side-effect of the album’s thematic center being the idea of death, the motifs of the supernatural and the mystical play major roles on the album. While Blackstar’s status as an experimental concept album may seem a departure from Bowie’s rock n’ roll past, the majority of the album, especially towards the last four tracks, maintains Bowie’s famous glam-rock tone along with all the other influences.

David Bowie takes on one clear form on this record, distinct from all his previous personas. He is Blackstar: a man who, without any explanation, follows a different path. As Bowie himself says on “Blackstar”, “I can’t answer why (I’m not a gangstar)/ But I can tell you how (I’m not a film star)/ We were born upside-down (I’m a star’s star)/ Born the wrong way ‘round (I’m not a white star).” But at the same time, he plays the role of Lazarus, who will be born again. This is not Bowie rejecting his own death, however. It is Bowie predicting that his principles will merely be reignited in another generation. Earlier in “Blackstar” Bowie sings, “Something happened on the day he died/ Spirit rose a meter and stepped aside/ Somebody else took his place, and bravely cried/ (I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar).” In “Lazarus” Bowie welcomes death with open arms, finally granting him the total freedom he had always aspired for. This is the total freedom from the weight of society along with the pain and suffering of his illness, “You know I’ll be free/ Just like that bluebird/ Now, ain’t that just like me?” The whole track “Lazarus” is fueled by prophecy. In it, Bowie accepts his own mortality in the opening line “Look up here, I’m in heaven.” Bowie concludes Blackstar with the track “I Can’t Give Everything Away” which features already solemn lyrics that are made more impactful by Bowie’s death, just like the album as a whole. In this conclusion Bowie reveals the unfortunate truth of his medium: that no matter how hard he tries he can’t bottle the entirety of himself into a record. Blackstar is a valiant, and in many ways successful, attempt to provide Bowie’s listeners a final glance at his truest feelings and personality, but it still falls short in Bowie’s eyes.

The generational impact that David Bowie’s music has had is palpable in any pop or rock in the modern day, his influence playing a key role in the development of the current musical landscape. Throughout the decades David Bowie has taken many forms, from The Thin White Duke to Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane. Perhaps his death, like that of the Biblical Lazarus, is not an endpoint, merely a transformation of form –from a mortal musical genius to a free and immortal legend.

Sidd’s Recommendations:

Aladdin Sane by David Bowie: Aladdin Sane is the defining work of Bowie’s early career. It’s hard to truly understand David Bowie’s legacy and the importance of Black Star as an album without knowing the rock star’s roots. Aladdin Sane is a personal favorite of mine, containing brilliant tracks such as “Aladdin Sane”, “Panic in Detroit”, and “Time”.

Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) by Brian Eno: Though Brian Eno is usually known for his work in ambient electronic music, a genre he himself had pioneered, his work is much broader. His production with David Bowie and other glam-rock artists influenced him heavily on Taking Tiger Mountain, a record that shows key rock and jazz influences in conjunction with Eno’s electronic expertise.

Image Source:

http://www.nme.com/news/david-bowie/89960