By Elizabeth Miller ’15, Co Editor-in-Chief

Back in Middle School, I used my laptop all the time. I did nearly all of my homework on it, and turned it in via OneNote. I took notes on my computer in all of my classes. Our teachers gave us websites and other online resources that aided us in and out of class. We had online textbooks so that we didn’t have to carry around thousands of heavy books from class to class. My entire school day revolved around my tablet.

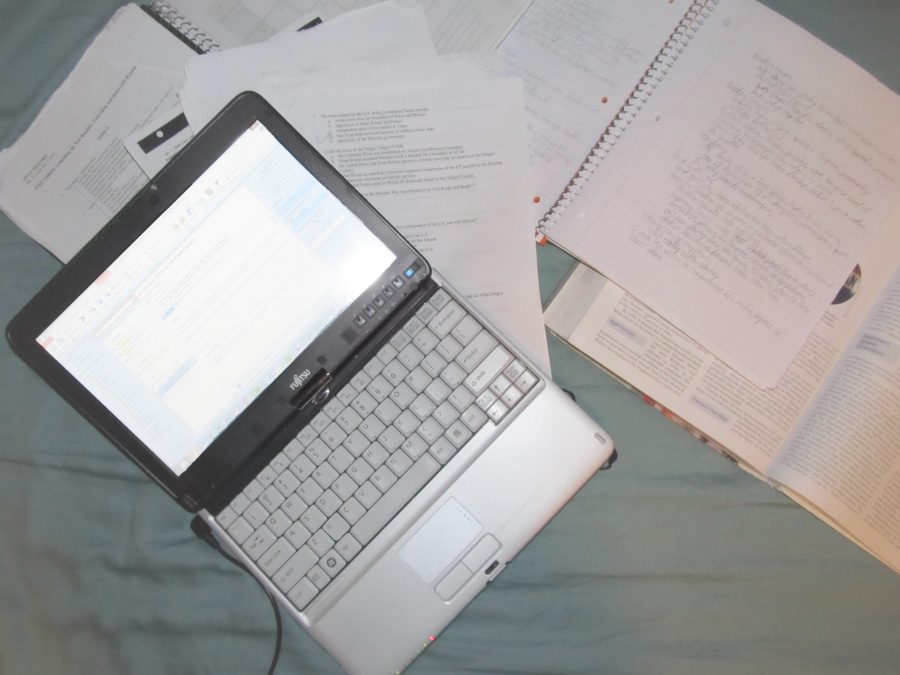

But ever since I entered the Upper School, my computer has sunk deeper and deeper into disuse. Some days, I spend more time listening to music on it while doing my homework (on paper) during free bells than I do actually making use of it for schoolwork, using my computer in only a couple classes, or even none. Many teachers won’t let students take notes on them during class (for legitimate reasons, such as the amazingly distracting internet) and insist that all of their homework and readings are completed using a hardcopy.

I understand that many of the teachers in the Upper School have been teaching in the same manner for years on end, and that they have made drastic changes to the way that they teach in order to try to incorporate the newly available technology. They use PowerPoints during class discussions, assign homework through the “portal”, and keep us up to date with e-mails. And yet, my laptop spends much of its day sitting untouched beside me on the table or shut up in my backpack. Of course, switching to the electronic world can be quite a pain, for using one’s computer to grade daily homework can be quite the hassle and finding electronic versions of sources is sometimes impossible. Nonetheless, if Middle School teachers have adapted, why can’t those in the Upper School?

In many ways, the more traditional classroom setup of a pencil and paper makes sense. As Upper School History Department Chair Merle Black (a strong believer in real paper reading packets and notebooks) explains, “Computers [can] put up a barrier between students and teachers, and students and students.” His classes revolve around give and take discussions that would be far more difficult to achieve if everyone’s eyes were glued to their computer screens. (In addition to which he points out: “We spend enough time in front of screens.”) Eye contact is necessary for the engaged and conversation-based classroom environment that is so iconic in a Mr. Black course. He still has his classes use their computers to write papers, look at art, and do research, but during a normal class, the only open computer in the room is his.

Dr. Jeremiah McCall, in contrast, is a leading part of the (slowly) growing population of high school teachers who use technology to better their classes in every way possible. Dr. McCall has always done his utmost to incorporate as much technology as possible into his courses. He strongly believes that computers “help out with a lot of things” in the classroom. His students take notes and do homework in a shared OneNote notebook, play history simulations with a video game program called Steam, watch video clips, and research using online databases. However, teaching history is not his only objective when it comes to the extensive computer usage in his classes. As he explained, “I’d love it if everyone in the school was comfortable using a computer,” and he helps his students towards achieving that goal by giving them as much experience with and exposure to computers as he can in his classes.

Clearly, there are inconsistencies in the use of computers in courses based on the teacher and his or her teaching style, varying from almost never using a computer in class to having the entire classroom center on students’ computers. This is something that Mr. Robert Baker, Country Day’s Director of Technology, understands, and in some ways appreciates. Teachers at Country Day have classroom autonomy, so they are allowed to teach what they want to teach in the way they want to teach it. When teachers want to use computers to make aspects of a class better, different, or more efficient, they have the ability to do that with the laptops. Although it would be wonderful for all classes to use it to the proper extent, Mr. Baker recognizes that it “would be a mistake to try and force it,” or to have teachers use technology merely for the sake of using it. His main goal for the tablet program is to “empower teachers and students” with the technology that is available to them.

It is clear that Country Day is a unique place when it comes to technology, even if one only looked at the number of computers in use at a school this size. It is viewed by many schools around the country (and the world) as the school to aspire to become, “the envy”, as Mr. Baker put it, of the technology-school community. However, the tablet program may not be as successful and omnipresent in the classroom as we often lead ourselves to believe.

There are so many opportunities that students and faculty have to use their computers to better their academic experiences that are completely ignored. Rather than giving students stacks of readings and worksheets, teachers could use OneNote shared notebooks or make better use of their Moodle pages. They could let students decide for themselves how they take notes in class, whether it be on paper or the computer, and could incorporate the incredible number of programs and resources available as software or on online databases. For the time being, completely transferring our academic world into a relatively small hunk of metal and plastic may be too optimistic, but in the future, would it be too much to find a balance?