Valentine’s Day: A Holiday for the Oppressed

February 6, 2021

February 14th. Valentine’s day. A day of love. A celebration of St. Valentine. A defiance of the state. A holiday for the oppressed.

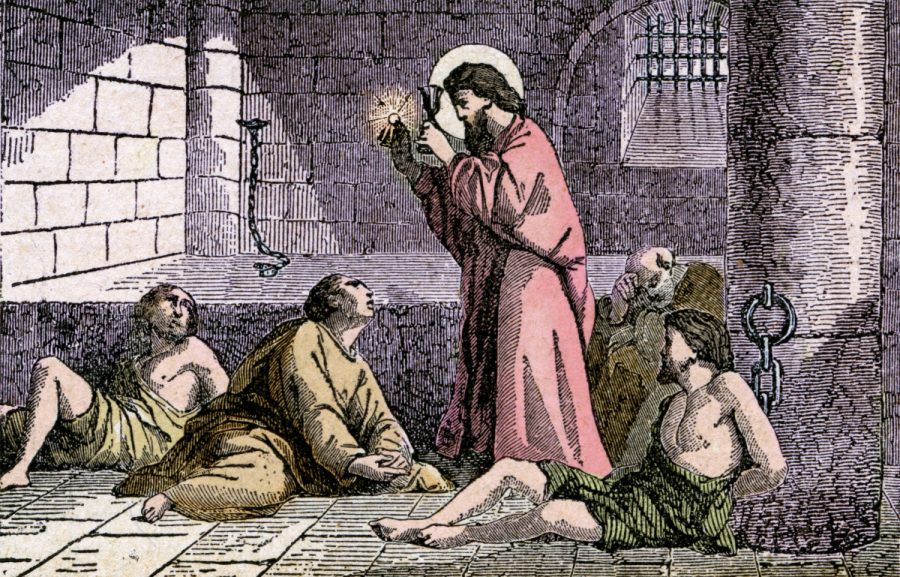

In the year 268, Army Officer Claudius II became the Emperor of Rome in the wake of skirmishes between his empire and invading tribes. To continue Rome’s defense, he needed a strong army: he needed young men. Claudius believed that single men made better soldiers than married ones. Thus, to strengthen his army, he passed a law banning the marriage of young men. He tried to outlaw love; St. Valentine would not let this stand.

In hushed voices and behind closed doors, St. Valentine performed marriages in secret. The defender of love continued to defy the emperor’s will until he was discovered. On February 14th, he was martyred. He stood up for what he believed in. He died for what he believed in.

This event, combined with the Pegan fertility celebration Lupercalia, is what gives us our February holiday. Though the day has become one of commercial love, the theme of the original story should not be forgotten.

When it comes to interracial marriage, the United States has a deep history of playing the part of Emperor Claudius. According to Alabama law in the 1880s, having a sexual relationship while unmarried was illegal, regardless of race. Laws, however, do not reflect reality: when it came to white couples, police turned the other eye. With interracial couples, it was a different story.

If any white person and any negro, or the descendant of any negro to the third generation, inclusive, though one ancestor of each generation was a white person, intermarry or live in adultery or fornication with each other, each of them must, on conviction, be imprisoned in the penitentiary or sentenced to hard labor for the county for not less than two nor more than seven years. (Alabama Code 4189)

Two centuries after the first ban on interracial marriage in the US, and a century before the Supreme Court abolished the bans nation wide, Tony Pace and Mary Cox met and fell in love in Grove Hill, Alabama. Their love was illegal. Mary Cox was a white woman, the vessel of white purity, the property of white men. Tony Pace was a Black man, a threat to the status of African Americans, a possible father to children that would blur racial lines. Interracial marriage bans were directly connected to slavery: their purpose was to enforce the racial hierarchy.

After meeting, the couple dated in secret until 1881 when they were discovered – likely by white neighbors – and arrested by the Clark County police.

Pace and Cox were tried separately and both convicted to two years of imprisonment on the grounds of “living together in a state of adultery or fornication.” Tony Pace – represented by lawyer John Tompkins – appealed all the way to the Supreme Court. Pace was the earliest example of anyone challenging the law, but not the last.

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. (US Constitutional Amendment 14, Section 1)

Tompkins argued that the conviction of Cox and Pace violated the 14th amendment. The court, however, was unwilling to touch the hierarchy. They said that interracial marriage was “evil” and led to “a mongrel population and a degraded civilization.” They rationalized this decision by ruling that, because both Cox and Pace had received the same punishment, the law did not discriminate by race. In 1883, the appeal was denied and Pace v Alabama remained the law of the land for nearly a century.

Tony Pace and Mary Cox had a life, but their place in history exists only in these few years. Upon reaching the Supreme Court, newspapers across the state gave the pair anywhere from a few sentences to a few paragraphs, but little is left on their life before or after. To the world their relationship was trouble; to the world they were nothing but a case.

Interracial is not the only love the United States has a history of forbidding.

In 1966, Richard Baker and James McConnell met at a barn party in Oklahoma. At that time, homosexuality was considered a disorder and sodomy was illegal almost every state. This was three years before the famous Stonewall Riots – an event that brought forth a new generation of LGBTQ activists – and Queer people mostly stayed hidden if they didn’t want to get attacked, arrested, or fired.

Baker was a field engineer who spent his childhood in a Catholic Boarding School after being orphaned at four. He later joined the air force, only to be kicked out when he was discovered to be gay. McConnell, in contrast, grew up in an accepting family and went on to get his Masters in Library Science. After the barn party, Baker and McConnell started dating and fell in love. In 1967, Baker proposed that they move in together, but McConnell accepted only on the account that Baker find a way to get them married – something that had never before been attempted in the United States. Two years later, Baker began studying law at the University of Minnesota, and McConnell joined on in a library position.

The couple applied for a marriage license in Minneapolis and were denied. However, gay marriage was so unheard of in 1970 that states did not have laws banning it. Maryland, the first state to ban interracial marriage, was also the first state to officially ban gay marriage in 1973. Despite this, Baker’s appeal was denied by the Minnesota Supreme Court in Baker v Nelson.

The case outed the couple. While Baker eventually became the first openly gay student body president at a major university, McConnell was fired from his library position at that same institution. It did not become illegal to fire someone for being Homosexual or Transgender until June 2020.

Despite these setbacks, the couple kept fighting. Searching for other ways to gain the legal privileges that married couples have, McConnell legally adopted Baker, giving them inheritance protections along with other rights. Next, Baker legally changed his name to “Pat Lynn McConnell” – a gender neutral title. Under this guise, the couple applied for a marriage license in Mankato, Minneapolis, to a clerk that did not know about the adoption nor their previous attempt. They were granted their license. On September 3rd, 1971 they were married by Reverend Roger Lynn at a private ceremony in their home city.

Six weeks later the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled that marriage is between a man and a woman, and a long line of state bans would soon follow. Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same sex marriage in 2003, but country wide legalization was not implemented until 2015 with Obergefell v Hodges. However, Baker and McConnell have lived happily as a married couple since that September day, and continue to fight for LGBTQ equality.

Moments Along the Fight

February 14th – St. Valentine is martyred as the protector of oppressed love

1691 – Virginia bans all interracial marriage

1922 – American-born Mary Das is stripped of her citizenship for marrying an Asian American

1967 – Interracial marriage is legalized nation wide

1977 – California bans gay marriage

1996 – Congress passes the Defense of Marriage Act, stating that federal marriage benefits are only accessible to heterosexual couples

2015 – Gay marriage is legalized nation wide

2021 – The fight for love continues

Works Cited

“A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: A Timeline of the Legalization of Same-Sex Marriage in the U.S.” Georgetown Law Library, 17 Jan. 2021, guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919&p=4182201.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Claudius II Gothicus.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Jan. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Claudius-II-Gothicus. Accessed 3 February 2021.

Faderman, Lillian. The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle. New York, Simon & Schuster, 2015.

“The Freedom to Marry in California.” Free to Marry, www.freedomtomarry.org/states/california.

“History of Valentine’s Day.” History.com, 20 Dec. 2009, www.history.com/topics/valentines-day/history-of-valentines-day-2.

“How Interracial Marriage Laws Have Changed since the 1600s.” ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/interracial-marriage-laws-721611.

Kelly, Kimberly Carter. “Defense of Marriage Act.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Mar. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Defense-of-Marriage-Act. Accessed 4 February 2021.

Maybury, Zach. “LGBTQ History Month: Jack and Mike, Our Pioneers.” MEUSA, 8 Oct. 2014, www.marriageequality.org/jack_mike_our_pioneers.

“The Same-Sex Couple Who Got a Marriage License in 1971.” The New York Times, 16 May 2015.

Schwallie, Kailey. “Talking Black and Sleeping White… Talking White and Sleeping Black: A Socio-Legal Examination of Interracial Marriage in America.” The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works, 2013, openworks.wooster.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=4782&context=independentstudy.

Stevenson, Bryan. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. Brunswick, Scribe Publications, 2015.

Totenberg, Nina. “Supreme Court Delivers Major Victory to LGBTQ Employees.” NPR, 15 June 2020.

“Validity of State Statute Forbidding Intermarriage of Races.” Albany Law Journal, vol. 27, Weed, Parsons & Company, 1883, pp. 215-16.

Wallenstein, Peter. “Race, Marriage, and the Law of Freedom: Alabama and Virginia 1860s-1960 – Freedom: Personal Liberty and Private Law.” Chicago-Kent Law Review, Dec. 1994, scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2967&context=cklawreview.