All Things Being Equal at the Cincinnati Art Museum

Hank Willis Thomas’s experience as a black man enriches his work with his own history and principles.

November 17, 2020

I had no idea what I was in for when I arrived on the second floor of the Cincinnati Art Museum to see Hank Willis Thomas “All Things Being Equal”. Thomas’s work, according to the museum, “asks us to see and challenge systems of inequality”. His multimedia exhibit, through printing, photography, sculpture, and textile work, explores gun violence the United States’ commodification of black athletes, the origins of race and racism, and the centuries-long struggle for equality in America and beyond. Thomas uses the lens of pop culture to further connect to his viewer, urging them to look critically at their society.

Two hours felt like mere minutes as I surveyed Thomas’s nearly 100-piece exhibit. I glided from one piece to the next, and could not help but think that each image, each sculpture, each miniature collection could be its own exhibit. That is what makes Hank Willis Thomas’s work and his exhibit so special. With his multifaceted approach to art, his refusal to bind himself to one medium, one concept, or one artistic style, he manages to tackle so many of the issues and indecencies of American society in the space of only three medium-sized gallery rooms.

Hank Willis Thomas’s experience as a black man enriches his work with his own history and principles. Unlike many other performative artists, like Tyler Shields, the white photographer behind the controversial and, in my opinion, insensitive, “Lynching”, image, Thomas does not have to extensively research his subject matter, he lives it. Having grown up as a black man in Plainfield, New Jersey, a city plagued by crime rates 80 percent higher than the rest of New Jersey, Thomas had to watch loved ones suffer as a result of the systemic racism of our country. Many of his pieces were inspired by the murder of his cousin, Songha Willis, who was killed in a violent robbery in 2000. Having lived the consequences in his own family, Thomas does not romanticize the effects of racism and gun violence on communities, on friends, and on families. In one of his most stirring pieces, “Bearing Witness: Murder’s Wake”, Thomas photographed those touched by the death and life of his cousin. In taking portraits of people Songha knew and loved, Willis Thomas attempted to create an incomplete portrait of his cousin. After gazing at every face, I read the heartbreaking description, stating that the many of the photograph’s subjects, too, had died from violence. Looking at the collage of portraits, I attempted to guess which of these vibrant and beautiful people had died, who was entitled to their own portrait of the grief of their loved ones. The cycle is never ending. One day it was Songha, and after he was grieved, death took his friends, his family, who would be grieved by their own communities, and so on. “When does it end?” I found myself asking.

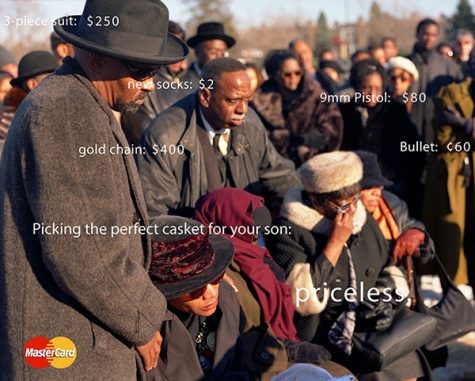

Hank Willis Thomas’s photograph, “Priceless #1”, taken at Songha’s funeral, displays the distress of grief in the context of a cool, capitalist America. As Thomas’s family wipes away tears and lean on each other for support, Mastercard’s now-ominous slogan hangs in the air above them. Mockingly, it reads:

3-piece suit: $250

New socks: $2

9 mm pistol: $80

Gold chain: $400

Bullet: ¢60

Picking the perfect casket for your son:

Priceless

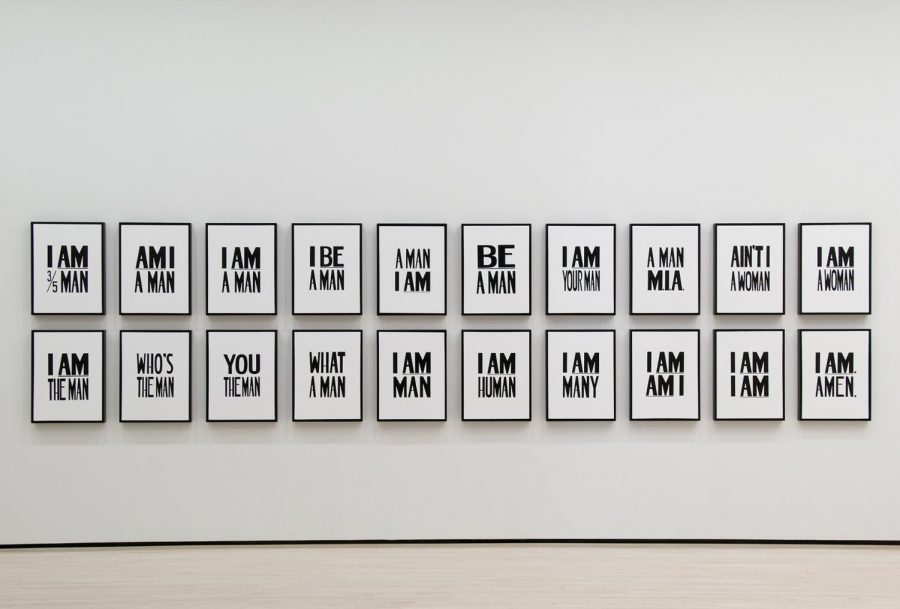

The meaning in Thomas’s work is not hidden. It is stated and written, not only in “Priceless #1” but also “I am. Amen”. This wall of twenty prints, labeled with bold text reading, “I Be A Man”, “I am a Man”, “I am 3/5 of a Man” and “I am Human” makes its point deftly, leaving the viewer speechless, silently questioning what it truly means to be an African American male in the United States, an identity that has been abused and ravaged by our society for decades. Like I said, the message is there, identifiable and accesible. According to Hank Thomas Willis, it is not simply about understanding the message or recognizing the depression. It is about using this information, using one’s voice, one’s eyes, one’s ears, and in my case, my own privilege, to make changes in American culture and society in general.