May Contain Content Inappropriate For Children: A Conversation of the Ethical Line that Video Games Cross (Part 3)

May 16, 2018

Jordann Sadler ‘18, Perspectives Editor

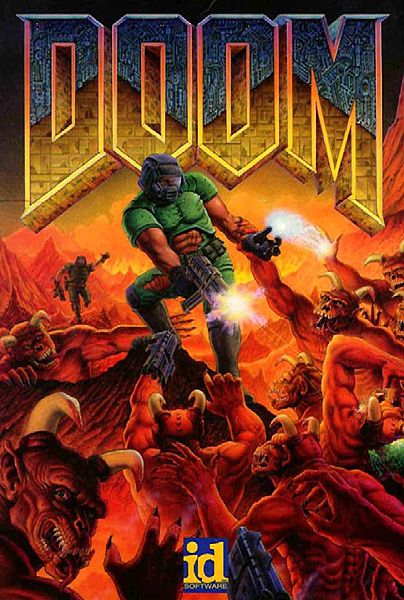

Doom, the grandfather of first-person shooter games, was thought to be satanic and demonic. Created in 1993 by id Software and release by GT Interactive, an unnamed space mariner fights his way through hell while shooting demons to pieces and chain-sawing his enemies. Many interviewees said that the game was doing the opposite since, in the game, you are killing these demonic creatures. Assuming one believes that Satanism is negative, you—the player—are not engaging in occult-like activities or partaking in demonic activities.

In addition to being rejected due to the imagery, the game was supposedly associated with the Columbine High School massacre in 1999 when Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold commented that killing would be “like playing Doom.” Jessie Lang ‘18 recalls the Slender Man incident when a girl stabbed her friend because of the popular Slender Man myth and “creepy pasta” story. This is an example of violence that is influenced by fictional characters. Often, video games, among other things, are often used as scapegoats for people’s actions. A game or myth alone cannot actively make someone murder or do horrible things. Usually there are other factors such as, mental instability, lack of parental guidance, bullying, access to weapons, etc., that cause children such as Klebold and Harris to commit horrible crimes. But, nevertheless, a video game can act as a sliver of encouragement, but it is not the prime factor.

Mr. McCall says that the Columbine Massacre is about “gun regulation and access to guns. Following more conscious parents…to blame a video game for a shooting is ludicrous. Parenting is critical.”

Kesler Stapp also adds that “in Doom you’re fighting against monster. They are not human. The lives are not human. If the people that shot up the high school thought those people were monsters, the problem is with the students that shot up Columbine, not Doom.”

The fear of first person shooters come from the thought that it is more personal. In third-person shooters, someone else is doing the actions, but in first person shooters, the camera is placed to seem as if you are the shooter/character. In this way, the violence is magnified. Alongside Doom, when speaking about first-person shooters, one might think of Call of Duty or Battlefield. Those games add more humanity because you are shooting other humans, but usually they are “the enemy”: Nazis, terrorists, war criminals, etc. As Noah Michalski ’18 says, “If it were humans, it would be mass genocide.” Doom becomes slightly more acceptable despite its rating because the player is killing monsters not actual humans.

The “connection” between video game violence and school shootings also seem to have a racial factor. The profile for the “standard school shooter” seems to be a white male who is a “loner,” as Lang describes them, and likes to play video games. The most common age of a school shooter is 17, but studies have shown that most perpetrators experienced a major loss and had a history of suicide attempts or suicidal thoughts. The white male “lone wolf” reflects on the population of video game users. The gamer population tends to be male, so it is not surprising that games are the first people would point to with the connection between the mentally unstable and violence. The cycle goes: a stimulus (death, relationship break-up, schizophrenia), exposed to violence (entertainment, bullying, unusual fascination with death, etc.), then access to violence (which is most commonly a gun).

Doom, amongst other violent games, have a M (17+) rating. For a child to have access to these games would be on the parents or the lack of regulation from video game retailers. One must also keep in mind, if a perpetrator is under 17 and happens to play violent video games, there is a lack of parental supervision which must be confronted in the household before it is confronted in the entertainment industry. If a teen was playing the appropriate age game and somehow Street Fighter (rated T 13+) induced a violent rage, then there would be an accurate complaint…but then, don’t let your child play it. Of course, it’s never that simple.

Adding to people’s fears, Doom has been rebooted with better graphics, more realism, and gore. Doom (2016) released by Bethesda studios and given a M rating is set to have a virtual reality game. “It makes you feel like you’re behind the weapon…It gets rid of the line between reality and fantasy. It makes that the reality,” says Lang. Games like these also play a part in releasing anger and bottled energy. As boxing and martial arts help or punching a pillow releases energy, video games can help. So, does boxing, the very definition of fighting for entertainment, make a person more dangerous or encourage violence?

“Boxing is a sport that I don’t watch, but there’s strategy. People get hurt but it’s also a sport. They train and choose to do that rather than depicting war which is something that one really doesn’t choose to do,” says Mrs. Jamie Back.

The discussion of video game violence also brings up a discussion of censorship and freedom of speech. Some defend hate speech with the first amendment and violent games are protected under that same Constitutional right. But, if a developer wants to make a provocative game, they are signing an unspoken contract that there will be criticism. Censorship has also been attacked, but usually the argument against censorship is that a piece of art (music, TV, etc.) is trying to tell a powerful message about society through its provocativeness or that censorship is turning a blind eye to the problems of the world rather than facing them head on. Therefore, censorship enhances the problems by preventing the much-needed conversation. Putting asterisks instead of letters, replacing the word ‘ni**er’ with ‘slave’, muting sexual innuendo and references in music—both those who are for and against censorship realize that there will be criticism. It seems that it’s harder to defend most video games because usually the violence is for violence sake, adrenaline, shock factor, or is just a mechanic of the game. Of course, that’s not the case for ALL games, but for controversial games that parents scoff at when they see its title, it is.

Setting a moral line in the video game industry is so difficult since being exposed to violence, absorption of violence, and reaction to violence is very contextual. Video games affect different people differently. Just like music (usually rap or metal) and television and film, it is hard to put a moral chain on games. Maturity, mental stability, moral compasses: society is as complex as the human mind.